Why do American coworkers always communicate so clearly and directly, but at the same time criticize rather indirectly and cushioned? When do Asian coworkers finally jump in and say something in a meeting? How do German coworkers get done anything innovative in their fixated planning madness? After having experienced many strange situations in projects with people from around the world, I found Erin Meyer’s book The Culture Map to be so insightful that I would declare it a must-read for any software professional who works with or in international teams.

Book & Author

The book is originally from 2014 but got its new yellow cover in 2016, which is still called the first edition. It presents 8 handy chapters distributed over ~290 pages.

Erin Meyer is a professor at INSEAD, one of the world’s leading business schools. After having lived in many parts of the world and having helped global leaders to manage the complexities of cultural differences, she presents this amazing book that explains the cultural differences that she studied in striking clarity.

Content and Structure

There are plenty of articles out there that discuss the differences between work cultures per country and also give handy tips about what to do and not to do in different cultures at work to not commit a blunder.

What this book makes different is that it does not simply explain “Colleagues from country A are like this and colleagues from country B are like that”. Instead, it categorizes certain traits which are common among all humans, and puts each work culture in relation to each other on one scale for each trait.

The Eight Scales

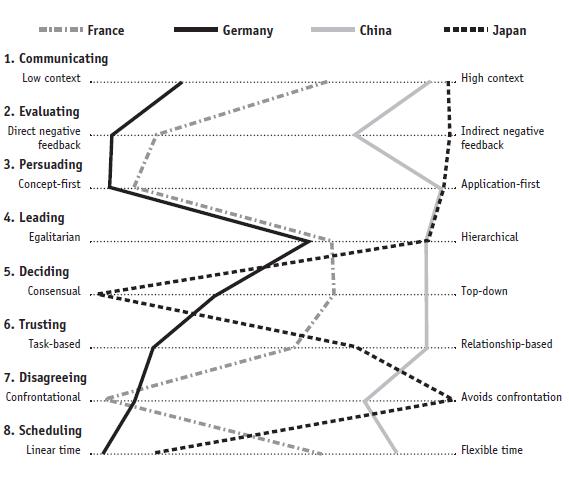

Erin argues that there are eight different traits that can be projected onto one scale each. Every scale’s extremes on the left and right describe opposing behavior/rules in certain scenarios:

Each chapter of the book explains one of the scales. The advantage of the approach to looking at these traits in isolation and then putting them together for each culture is that each chapter is short, comprehensible, and easy to memorize. On top of that, it is relatively simple to assess cultures that are not treated in this book on this map of scales.

Apart from per-country culture, many companies have developed their own work culture which may be different from companies in the same country, but can be explained quickly and efficiently to outsiders.

Let’s get to these traits. I will briefly summarize them and maybe give some highlights, but apart from a few highlights, won’t cover the long list of practicable advice from the full book. Every trait is also presented with a scale that positions each country according to its culture.

- 1.) Communicating: Low-Context vs. High-Context

-

Different cultures have a different perspectives on what good communication means:

- Low-Context:

- Precise, simple, clear.

- Messages are expressed and understood at face value.

- Repetition is appreciated if it helps clarify the communication.

- High-Context:

- Sophisticated, nuanced, and layered.

- Messages are both spoken and read between the lines.

- Messages are often implied but not plainly expressed.

An interesting perspective covering this scale is that the low-context communication style could be taken as an affront to high-context people because it can make them feel “This simple and redundant language gives me the feeling that they think I am stupid.” – while the other way around might be like “This layered language gives me the feeling that I am not trustworthy, otherwise they would just speak straight.”, or “If the matter was important to them, they would be more direct about it.”

A rule of thumb is that humans from countries with very old history and to some extent isolation share a lot of context in their language, giving them the possibility to say more with less. People with very different backgrounds don’t have as much common context, hence the need for more precise communication.

- 2.) Evaluating: Direct Negative Feedback vs. Indirect Negative Feedback

-

This scale is about different ways to give negative feedback:

- Direct

- Negative feedback to a colleague is provided frankly, bluntly, and honestly.

- Negative messages stand alone, not softened by positive ones.

- Absolute descriptors are often used when criticizing. (e.g. “totally inappropriate”, “completely unprofessional”)

- Criticism may be given to an individual in front of a group.

- Indirect

- Negative feedback to a colleague is provided softly, subtly, and diplomatically.

- Positive messages are used to wrap negative ones.

- Qualifying descriptors are often used when criticizing. (e.g. “sort of inappropriate”, “slightly unprofessional”)

- Criticism is given only in private

Especially cultures that are at the same time low-context and direct-negative-feedback, like the US and UK, at first sight, seem like a strange combination but are well explained in this chapter.

What is more important when giving good criticism? Making sure that it is conveyed politely at the price of maybe being overlooked or not understood to the full extent – or conveying it in its clearest form, which also emphasizes a form of trust on the strength of the (work) relation?

- 3.) Persuading: Principles-First vs. Applications-First

-

Here, it is about how new ideas and approaches are explained to an audience:

- Principles First

- Individuals have been trained to first develop the theory or complex concept before presenting a fact, statement, or opinion.

- The preference is to begin a message or report by building up a theoretical argument before moving on to a conclusion.

- The conceptual principles underlying each situation are valued.

- Applications First

- Individuals are trained to begin with a fact, statement, or opinion and later add concepts to back up or explain the conclusion as necessary.

- The preference is to begin a message or report with an executive summary or bullet points.

- Discussions are approached in a practical, concrete manner.

- Theoretical or philosophical discussions are avoided in a business environment.

I found this distinction not only to be valid when talking to humans of different cultures but also when talking to professionals from different departments.

This part of the model does not fully apply to Asian cultures, to which the chapter devotes another subsection.

- 4.) Leading: Egalitarian vs. Hierarchical

-

Different cultures prefer different leading styles:

- Egalitarian

- The ideal distance between a boss and a subordinate is low.

- The best boss is a facilitator among equals.

- Organizational structures are flat.

- Communication often skips hierarchical lines.

- Hierarchical

- The ideal distance between a boss and a subordinate is high.

- The best boss is a strong director who leads from the front.

- Status is important.

- Organizational structures are multilayered and fixed.

- Communication follows set hierarchical lines.

This chapter is especially interesting for the reason that it is easy to accidentally undermine someone’s feeling of authority by e.g. skipping the hierarchy when mailing questions to people etc. Also, in hierarchical cultures, it may be pointless to ask about peoples’ opinions in the presence of their boss. This chapter is full of examples and advice.

- 5.) Deciding: Consensual vs. Top-Down

-

How are decisions formed in organizations?

- Consensual: Decisions are made in groups through unanimous agreement.

- Top-Down: Decisions are made by individuals (usually the boss).

The principle is straightforward but the most interesting case are cultures that combine strict hierarchy with consensual decision-making. The strongest example of this is Japan with its Ringi-Process, but this is only the strongest example of many (Germany also cultivates a bit of this mixture).

My highlight of this chapter is the big D vs. little d model that helps explain to people from cultures that are at opposite ends of this scale, what kind of decision is needed or made when. When a big D decision is made, then it is to be seen as strict, while a little d decision allows for flexibility even after the decision was made. This distinction helps set expectations of groups that appear chaotic or inflexible to each other. The big D vs. little d model helped in the collaboration between US-American and German teams in one of the book’s examples. I really felt this one.

- 6.) Trusting: Task-Based vs. Relationship-Based

-

How do people build trust?

- Task-Based

- Trust is built through business-related activities.

- Work relationships are built and dropped easily, based on the practicality of the situation.

- “You do good work consistently, you are reliable, I enjoy working with you, I trust you.”

- Relationship-Based

- Trust is built through sharing meals, evening drinks, and visits to the coffee machine.

- Work relationships build up slowly over the long term.

- “I’ve seen who you are at a deep level, I’ve shared personal time with you, I know others well who trust you, I trust you.”

I felt this difference myself while working for US-American companies that also have for example Indian offices. Collaborating with my Indian colleagues got much better after getting to know them in person at dinner, while I got to know my American colleagues only at office times. The book also explains that especially in Asian cultures it can be beneficial to drink together: Having seen each other with guards down increases trust on a personal level.

Another highlight of this chapter is the Peach vs. Coconut principle: People from different cultures might misinterpret friendliness as too much of an invitation for a personal connection or an offer of friendship, which might look “fake” to them. In that regard, peach cultures are friendly and soft with people they have just met, but the real self stays protected professionally. Coconut cultures in contrast present a hard protecting shell at first but an even softer core inside (once you got through the shell).

- 7.) Disagreeing: Confrontational vs. Avoids Confrontation

-

How do colleagues disagree?

- Confrontational

- Disagreement and debate are positive for the team or organization.

- Open confrontation is appropriate and will not negatively impact the relationship.

- Avoids Confrontation

- Disagreement and debate are negative for the team or organization.

- Open confrontation is inappropriate and will break group harmony or negatively impact the relationship.

Confrontational cultures are also emotionally more expressive, which can be overwhelming for people of different cultures – what looks like a normal discussion to one can seem to another like a fight that is about to break out.

As the styles of disagreeing and decision-making can cause incompatibilities, especially in big international companies, the chapter explains how to deal with this on large scale, and how to present decisions/discussions to a mixed audience.

- 8.) Scheduling: Linear-Time vs. Flexible-Time

-

How do cultures approach plans, projects, and appointments?

- Linear Time

- Project steps are approached sequentially, completing one task before beginning the next.

- One thing at a time. No interruptions.

- The focus is on the deadline and sticking to the schedule.

- Emphasis is on promptness and good organization over flexibility.

- Flexible Time

- Project steps are approached fluidly, changing tasks as opportunities arise.

- Many things are dealt with at once and interruptions are accepted.

- The focus is on adaptability, and flexibility is valued over organization.

Living in Germany, I regularly see two different kinds of linear planning extremes:

- Planning everything down to the smallest detail.

- Sticking to a plan no matter what, even if the circumstances that led to this plan, changed.

Planning has advantages, but flexibility has advantages (hello lean and scrum), too, and different cultures picked their favorite. It seems that the political history of countries has affected the planning mentality of their citizens.

This chapter puts some effort into giving tips on how to combine both in multicultural companies.

Aren’t Stereotypes Racist?

For some, the book may trigger the question, of whether books like this may propagate a school of thought that facilitates box-thinking or even racism. Erin addresses these worries in the introductory chapter:

After I published an online article on the differences among Asian cultures […], one reader commented, “Speaking of cultural differences leads us to stereotype and therefore put individuals in boxes with ‘general traits’. Instead of talking about culture, it is important to judge people as individuals, not just products of their environment.”

This is indeed a good point, but her answer puts it in a great perspective:

If you go into every interaction assuming that culture doesn’t matter, your default mechanism will be to view others through your cultural lens and to judge or misjudge them accordingly.

Summary

As so often with books about culture and psychology, there are no big surprises in it, or nothing completely new. The value I took out of this book is that it puts everything in a structured perspective that I would not have come up with myself. After reading through it, I felt inspired and empowered on how to deal with cultural differences in the future, and get more out of intercultural collaboration!

Apart from cultural differences, many people within the same/your country show different traits that can be found on the presented scales, too. It helps make sense of behavior that could otherwise be considered strange. It is easier to show empathy when you understand where people are coming from.

I declare this book a must-read for every (not only) software engineer professional who works internationally.