This article is about a little interesting detour that I made in one of my personal projects: How to use strong type systems to generically apply a binary mathematical function on all items of a possibly nested record. The code provides interesting insights into other languages with similar type systems.

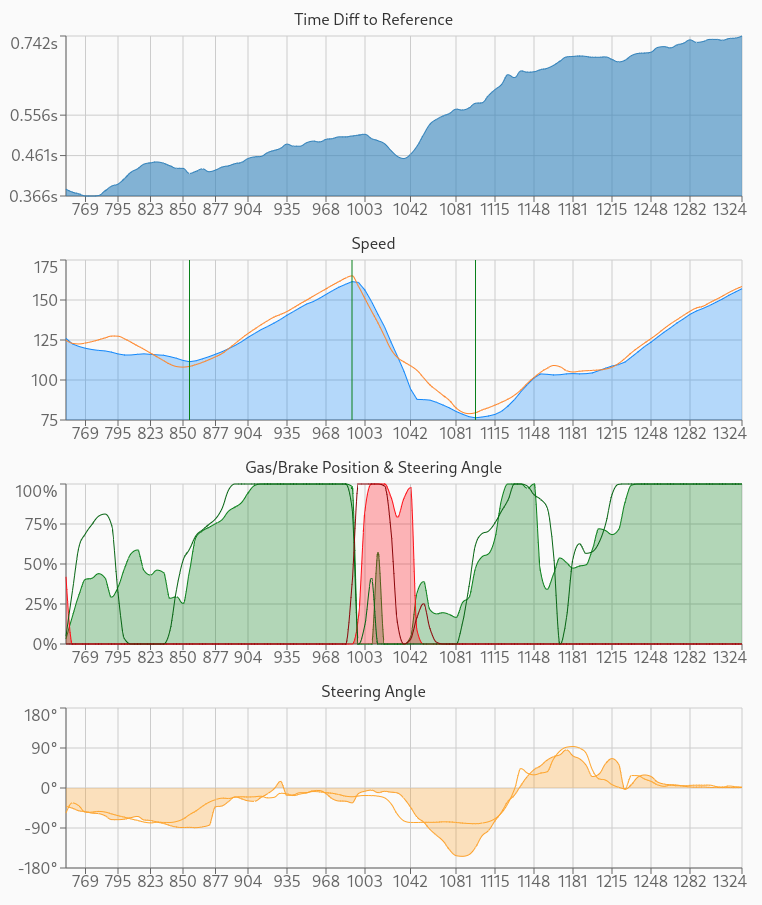

In this personal project, I work with numeric data that is displayed in diagrams like these in the user’s browser:

The amount of input data can be huge at times and needs post-processing for the following reasons:

- Displaying too much data gives longer render times and stuttering movement when scrolling or hovering over the data points, especially on smartphones or older computers

- More detailed data does not always lead to visibly more detailed diagrams anyway

- To compare two diagrams at the same data grid positions, the dataset of one diagram needs to be interpolated into the other

For these reasons I wrote a few functions that post-process the data in the following steps:

- Create the mathematical derivative of the data

- Thin out the data of the first diagram by skipping samples that have the lowest derivative values. This way the most detailed areas in the data stay detailed enough, but the data gets much lighter.

- Interpolate the data of the second graph onto the resulting data grid positions of the first diagram.

The data is represented as arrays of records in PureScript:

type TelemetrySample =

{ position :: Number -- Relative position on the track

-- between 0.0 and 1.0

, speed :: Number -- km/h

, gasPedal :: Number -- Value between 0.0 and 1.0

, brakePedal :: Number -- Value between 0.0 and 1.0

, steeringWheelAngle :: Number -- Degrees

, tirePressures :: Array Number -- List of four PSI pressures

, tireTemperatures :: Array Number -- List of four °C temperatures

, ...

}Having so much data on many different things like speed, pedal positions,

steering wheel, etc. means that steps 1-3 would need to be performed on all

these attributes for each diagram.

Interestingly, applying some knowledge of the actual domain the data comes from

helps out:

The interesting data is in the corners when the car gets slower and faster

quickly.

The long straights where the driver just drives full-throttle and does only

slight corrections with the steering wheel can be thinned out.

This means that the derivative of step 1 can be the derivative of the position

data, which shows low values when the car is slow, so we would keep those

values on the diagram.

An alternative is the derivative of the speed, which shows low values when the

car’s speed isn’t changing a lot (like on the straights), so we would drop

these values.

Step 2 can be performed repeatedly: One would first sweep data carefully with a low threshold, and if the number of samples is not low enough, then just repeat with a higher threshold, until the size of the data is good enough for fast rendering.

Step 3, interpolating data, can be done by simple linear interpolation between two neighbor data points, or by including even more data points using polynomial interpolation or Fourier synthesis. I chose to try the cheapest method - linear interpolation - first. It turned out to be good enough.

Linear Interpolation

Linear interpolation is adding two values after adapting their weight in the final result: If we need the middle between two data points, we would divide both of them by 2 and add them together. If we want the data at a 3/4 position between two points, we would take 1/4 of the first point and 3/4 of the second point, and so on.

In PureScript, Haskell, ML, or any language that has

type classes, we can declare a

class Lerp (for Linear Interpolation) and implement it for the

Number type like this:

class Lerp a where

lerp :: Number -> a -> a -> a

instance lerpNumber :: Lerp Number where

lerp n a b = a + (b - a) * nThe lerp function accepts a parameter n which describes the relative

position to interpolate to between the two points that are the other two

parameters:

> import Lerp

> lerp 0.1 0.0 10.0

1.0

> lerp 0.5 0.0 10.0

5.0My input data is also represented by Int and Boolean points.

Integers can be cast to floating point Numbers, lerped on their domain, and

then be brought back to Int by rounding.

The same can be done for Boolean values, which is a bit of a tongue-in-cheek

method, but on the given data domain this is fine for my purposes:

instance lerpInt :: Lerp Int where

lerp n a b = round $ lerp n (toNumber a) (toNumber b)

instance lerpBoolean :: Lerp Boolean where

lerp n a b = from $ lerp n (to a) (to b)

where

to = if _ then 1.0 else 0.0

from x = round x > 0For integers, this works as expected.

For booleans, we accept that due to quantization, 0.1 * true equals false:

> lerp 0.5 0 10

5

> lerp 0.55 0 10

6

> lerp 0.1 true false

true

> lerp 0.9 true false

false

> lerp 0.5 true false

trueLerping arrays of values that are in the type class already is not much work: One type class instance can be implemented in terms of the other, which is where nice type systems create a lot of joy:

instance lerpArray :: Lerp a => Lerp (Array a) where

lerp n a b = zipWith (lerp n) a bNow everything is ready to lerp whole records of data, but wait:

lerpRecord :: Number -> TelemetrySample -> TelemetrySample -> TelemetrySample

lerpRecord n l r =

{ speed = lerp n l.speed r.speed

, gasPedal = lerp n l.gasPedal r.gasPedal

, brakePedal = lerp n l.brakePedal r.brakePedal

, steeringWheelAngle = lerp n l.steeringWheelAngle r.steeringWheelAngle

, ...

}With a rising number of attributes in the record type, this gets very

repetitive, error-prone, and ugly very fast!

As soon as the record is nested, we would need another function for each of

them.

I wanted to be able to call the function lerp on records of data, assuming

that all record member types have instances of the Lerp type class.

At this point this would bring me:

- Eliminated repetition

- Eliminated potential for typos

- Learn how to implement such a mapping for generic records

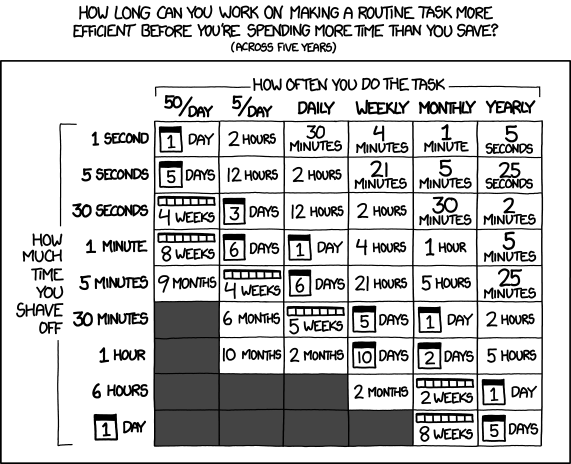

On the one hand, according to the famous XKCD comic “Is it Worth the Time?”, I really should not do it, because the repetition is still not getting out of hand. On the other hand, I like metaprogramming and learning the programming languages that I use regularly thoroughly, so I decided to invest an afternoon into learning how to do it.

Mapping Functions over Records of Data

What we are aiming at is running the lerp function over records of values:

> r1 = { a: 1, b: 1.0, c: { d: 10.0 } }

> r2 = { a: 10, b: 2.0, c: { d: 20.0 } }

> lerp 0.5 r1 r2

{ a: 6, b: 1.5, c: { d: 15.0 } }The journey of getting there had striking similarities to the other little adventures I blogged about, namely mapping over heterogeneous type lists in Haskell, or implementing a compile-time Brainfuck interpreter in C++ template language. In many ways, generic data handling is similar in many programming languages.

In PureScript, records

are a data type that can be transformed into a RowList at compile time.

A RowList is a cons-style list

of items that point recursively to the next item until the last item points to

a special Nil terminator item.

In the RowList case, every item practically conveys the key and the value of

each record member.

This means that we need to implement a type class that decomposes a record into

a heterogeneous list of items that then recursively get mapped over our lerp

function:

class

LerpRecord

(rl :: RL.RowList Type) -- 1.) Class Parameters

(r :: Row Type) --

(from :: Row Type) --

(to :: Row Type) --

| rl -> r from to -- 2.) Functional dependency

where

lerpRecordImpl -- 3.) Interface

:: Number

-> Proxy rl

-> Record r

-> Record r

-> Builder { | from } { | to }This looks very complicated, so let’s go through it step by step:

Beginning with line 3.) we see the signature of the function that we create.

This function accepts a proxy of a RowList and the two same-typed records that

we are going to lerp.

It returns a function that constructs a record with lerped fields and will be

later consumed by the build function of the purescript-record library.

We get to the builder pattern after the next code excerpt.

The first four lines that are commented with 2.) are the type class parameters,

and thanks to the

kind system

in PureScript, they are constrained to what we intend this class for.

The functional dependency

in 2.) says that all types can be deduced from the

rl type, so the compiler can catch us filling in the wrong types.

Using this class, we can now create a function lerpRecord that has the same

interface as our basic lerp function, but for records:

lerpRecord

:: forall t r

. RL.RowToList r t

=> LerpRecord t r () r

=> Number

-> Record r

-> Record r

-> Record r

lerpRecord n a b = Builder.build builder {}

where

rowList = Proxy :: _ t

builder = lerpRecordImpl n rowList a bHere we can see that the lerpRecordImpl function makes us a builder function

from both input records a and b, which we then use to return the lerped

record to the end user.

The Proxy constructor helps us putting the type-level information of t into

the variable rowList, so we can feed it into the function lerpRecordImpl.

In the LerpRecord t r () r line, we say that we need a builder function that

gets us from an empty record “()” to the final record type r.

While lerpRecordImpl could create many other build functions, we select this

one.

Now, we can use the type class LerpRecord and the function lerpRecord to

make all lerpable records an instance of the earlier type class Lerp:

instance lerpRecordInstance ::

( RL.RowToList a t

, LerpRecord t a () a

) =>

Lerp (Record a) where

lerp = lerpRecordThe type constraints are the minimal guidance that the compiler needs to select

the right type class instance for us when we call lerp on a record.

We “only” need to implement lerpRecordImpl now.

The abort case on the end of the RowList is simple:

instance lerpRecordNil :: LerpRecord RL.Nil trashA () () where

lerpRecordImpl _ _ _ _ = identityWhen the recursion is called on the list tail, we return the identity

function.

Every build step is meant to transform from a smaller RowList to a bigger one,

by appending another item.

The Nil step just does nothing.

The other recursion steps are performed in one other implementation of the

lerpRecordImpl function, which is the most complicated but last piece of

today’s puzzle:

instance lerpRecordCons ::

( LerpRecord t r from to' -- Constraints, 1

, IsSymbol k -- 2

, Row.Cons k a trashA r -- 3

, Row.Cons k a to' to -- 4

, Row.Lacks k to' -- 5

, Lerp a

) =>

LerpRecord (RL.Cons k a t) r from to where

lerpRecordImpl n _ a b = current <<< next

where

current = Builder.insert key lerpedValue

next = lerpRecordImpl n tail a b

lerpedValue = lerp n (R.get key a) (R.get key b)

key = Proxy :: _ k

tail = Proxy :: _ t

Whenever lerpRecordImpl is called with some parameters, the compiler

“searches” for the right implementation.

The section commented with “Constraints” gives the compiler the following

constraints when asking “is this the right implementation for this call?”:

- Given parameters match for the next recursion step, where

to'is thetoversion of the next deeper recursive call. - The key element of a

RowListitem is a “symbol”. TheR.getfunction that we use later needs that. - A

Conspart of aRowListcan be constructed from our key typek, the value typeaof one item and the recordr.trashAmeans that we don’t care what the tail is, as this constraint is only for verifying that ourConshead contains what we need. - Prepending the key-value pair to the

to'type leads to the currenttotype in the builder chain that describes the recursion level we are currently looking at. - The

to'type in the builder chain does not contain the keykalready. - The

atype in the currentConshead has an instance of type classLerp.

The compiler will only select this function if all the constraints match. It essentially creates two functions and returns their concatenation:

currentis a builder function that inserts the lerped values for the current record key at the current recursion level.nextis the function that contains the same concatenation of the next recursion level.

What remains magic is the handling with the Proxy types:

We need them to get at the key value and the tail of the row list which gets

shorter with every recursive call.

The Proxy type constructor accepts type-level information and gives us nice

variables from that.

This way we can feed the key variable to the R.get function from the

RowList library to obtain the current record item for lerping, and use tail

as a parameter to lerpRecordImpl for the next recursion call.

The unit test for the final lerp of a nested record structure proves that it works:

it "correctly lerps nested records" do

let a = { a: 0.0

, b: 0

, c: { d: 0.0 , e: false }

}

b = { a: 10.0

, b: 10

, c: { d: 10.0 , e: true }

}

c = { a: 7.0

, b: 7

, c: { d: 7.0 , e: true }

}

lerp 0.7 a b `shouldEqual` cSummary

We ended up with more code than the “manual” record lerp function, but this little quest was great for learning how to do it. Two type classes later we got a function that works even on nested records.

Interestingly, such type-level programs look similar in all the languages that provide sufficiently mighty type systems, so this is nothing that one learns for one language and then never needs again.

While I was learning how to do this, other PureScript users from the

PureScript Discord Server pointed me to the

purescript-heterogeneous

library:

This library provides functionality for mapping over heterogeneous lists.

Essentially, a RowList is a heterogeneous list, so by using this library it

should be possible to provide the same functionality with less code (by

transforming a record to a RowList, then use such libraries on that, and

convert it back to a record).

But this would be material for another blog article.

The full working code together with build instructions is on GitHub: https://github.com/tfc/purescript-ziprecord