Software engineering, or generally IT jobs, are highly social because all big software projects or products are built by teams of professionals. When humans work with humans, all kinds of conflict can emerge, and they are often not as easy to fix as IT problems, especially in distributed teams with less offline human interaction. This article is about Fritz Riemann’s book “Anxiety”, which answers the question “What do people fear and how do they cope with it?”.

Book & Authors

Link to the Amazon Store Page of the English version

Link to the Amazon Store Page of the original German version

The book was initially published in German in 1961 and since 2022 its 47th edition is sold, while its English translation was published in 2009. Both versions are a bit more than 200 pages. I have read the German version of the book. The English version is advertised as a 1:1 translation.

Fritz Riemann was a German psychologist, psychoanalyst, and book author. In 1946, he co-founded the Institute for psychological research and psychotherapy in Munich. Riemann became an honorary member of the Academy of Psychoanalysis New York.

Content and Structure

This book is from a psychologist for non-psychologists. People go to places, found companies, quit their job to apply for new ones, build houses, give talks, etc., for reasons. According to Riemann, people sometimes do these things as a reaction to fear. Especially when people work or live together, all kinds of conflicts emerge due to differences in their characters. What appears normal to one might trigger fears in another. This can especially happen in international teams due to cultural differences but for that topic have a look at my book review of “The Culture Map”.

Fritz Riemann explains his model that I call the “Riemann Model” over the rest of this article.

The Model

No model is a silver bullet but knowing in which situations to apply what model or at least take it as a rough guide often proves useful. Riemann postulates that there are different Personality Types based on different atomic fears and needs that each individual has. People’s lives are driven by their fears, some more than others. These fears and needs are:

| Fear | Need | Experienced as |

|---|---|---|

| Fear of self-surrender | Need to be an individual | loss of self and dependence |

| Fear of self-realization | Need to be part of a group | isolation and lack of emotional security |

| Fear or necessity | Need for change | finality and lack of freedom |

| Fear of change | Need for continuity | transience and insecurity |

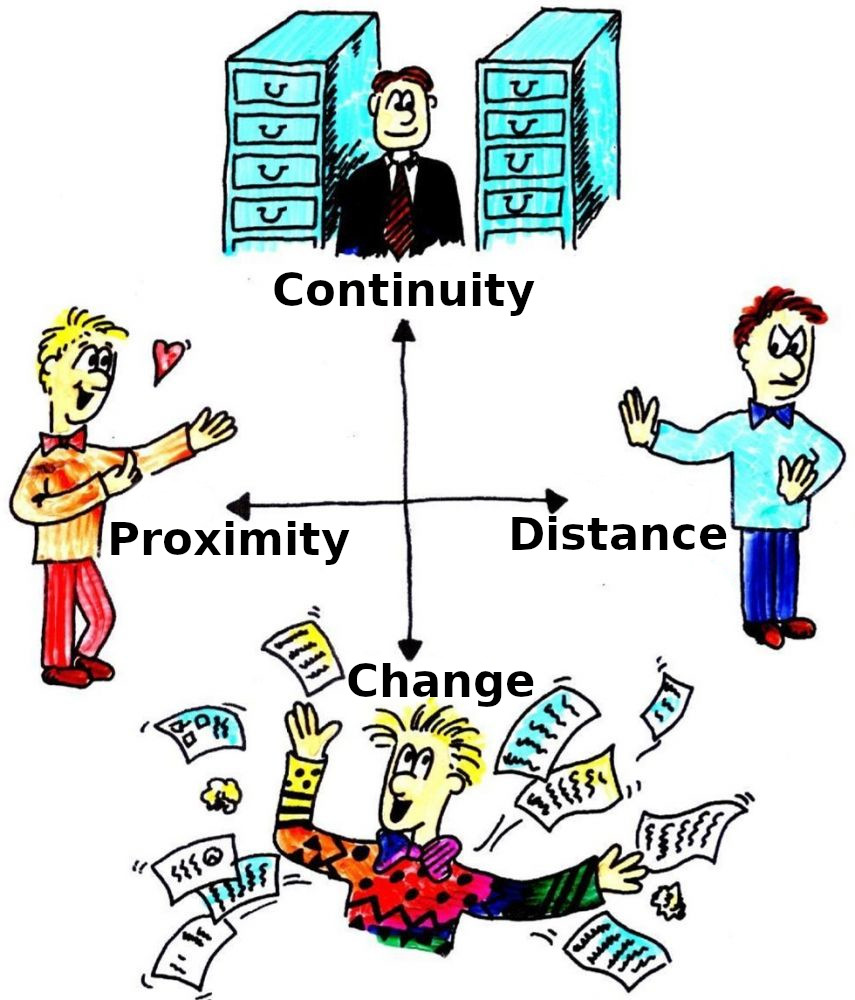

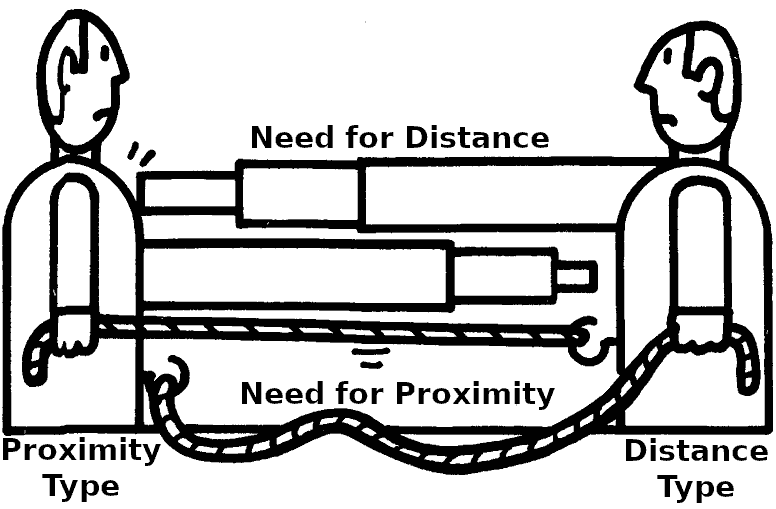

Regarded as pairs, they form two conflicting poles that can be visualized as a diagram:

- Emotional distance vs. proximity from/to others

- Change vs. continuity

The book puts some emphasis on explaining the extremes of these characters first. These are explained in 40-50 pages each, so if the summarized presentation in this blog gives the impression that the topic is dealt with like in a magazine checklist, then this is due to the abridged presentation. These explanations seem very pathologic at first glance because the book is not about mentally sick but healthy people. The point of this pathological view is that understanding the extremes improves comprehension of such traits when observing them in real life, although of course not in the depicted extremes. For every character trait, Riemann gives a very rich and detailed overview of the trait but also delves into how they deal with love and aggression and gives examples of how they experience typical situations in life. These chapters are explaining it all so well that it hurts to provide only a short and simplified explanation here, but that’s why one reads whole books instead of summaries anyway. I am pretty sure that everyone will recognize themselves in all chapters to some degree, but in different severity. At last, he also explains what situations and events in early life cause the development towards each pole. Let’s summarize every trait into caricatures to have an overview:

- Schizoid Personality (Distance)

-

Schizoids want and need to be seen as individuals (have you ever been irritated when someone got your name or gender slightly wrong?). They fight for their freedom and independence. For that reason, they feel the need to avoid compromise and commitment. Keeping enough emotional distance from everyone is on the one hand like a defense mechanism against everything that reduces their freedom and independence. Talking about emotions: They don’t like them much and see pure cold rationality as a cure - which is a strength and weakness at the same time. However, proximity to others is unavoidable, so they end up developing some protective stance that might often look impersonal and cold to others. Schizoids often drift into isolation, as this is what they rescue themselves into after conflicts with others. While behaving how schizoids behave, they can look aggressive from the perspective of others, which might also be intimidating.

Such shields are a result of their past: They most likely experienced too much pain in dependent relationships in their young years and grew independent to free themselves from it.

Typical traits or attributions by others: Aggressive, arrogant, cold, isolated, objective, strong self-esteem, task-oriented, criminal, anti-social

- Depressed Personality (Proximity)

-

“Depressed” people have a deeply embedded wish for affection and emotional proximity to others, literally all the time. “I love you because I need you” and “I need you because I love you” are two equally true statements for them. All distance that Schizoids try to build up, Depressed try to tear down as it feels like loneliness and being forgotten to them. To counter their separation anxiety, they build up all kinds of dependency on others, towards which they also form expectations - which they won’t explain because they see that as an indicator of not being understood. Depressed often end up blaming others for their situation - the obvious way to work towards a solution independently triggers their separation anxiety so they “can’t”. They hope that when they lament their problems, someone will help them. Most of the time, help is not what they ask for when they keep lamenting about their problems - it’s affection in the form of listening and empathy. To others, this often looks like learned helplessness, self-pity, a lack of direction, and clumsiness.

Deep inside, depressive parents don’t want their children to grow up and become independent because this bears the potential for the distance they fear. So they sometimes end up raising spoiled children with a lack of skills to master life on their own, which produces the next generation of depressive humans.

Typical traits or attributions by others: Indecision, Blaming others, insecure, warm, needy, clingy, caring, dependent, subordinate, people-oriented, empathic, envy, resigning, self-hate, depression, suicide

- Compulsive Personality (Continuity)

-

Compulsive characters fear changes and unplanned events. They are on a quest for permanence and security. For that reason, they enjoy planning ahead everything in meticulous depth, to be prepared even for events that may probably never occur. Changing plans even in light of changed circumstances is difficult for the compulsive. Enduring the costly trade-offs of a local optimum is much easier for them than trying a promising new solution because it might introduce new unforeseen problems. New ideas are always evaluated in terms of how they help support the Old World. The lack of control over life and the future is a burden. When compulsive people catch themselves in the act of giving in to temptation or losing control of their emotions in an argument, guilt plagues them for a long time.

Strict parents instill in their children the need for planning, control, and security by constantly admonishing them about order, punctuality, and compliance from an early age. In later life, the ever-admonishing feeling remains in the back of their mind.

Typical traits or attributions by others: Reliable, dutiful, precise, rigid, jealous, fanatic, despotic, pedantic, prejudice, perfectionism, responsible, diligent, tidiness, parsimony

- Histrionic Personality (Change)

-

Histrionics fear stagnation. It does not matter if everything is fine where they are: They want to experience new things, travel to new places, and try out new ideas. That the unknown does not always bear good things is irrelevant: It’s change what they are after, change for its own sake. Making no plans helps histrionics to concentrate on the moment, free from the obligation to express what goal would be achieved by what they are doing. They don’t find security at all convincing because they are busy trying to free themselves from rules and compromises. In between their chaotic life they are nonetheless very charismatic and charming. But don’t feel too flattered if they tell you confidential gossip as you’re one of many listeners providing them attention.

Milieus that are chaotic, contradictory, incomprehensible, and/or without guidance and healthy models give the child too little orientation and support. In such environments, children learn: “If they don’t love you enough when you’re easy and uncomplicated, then their concern for you will get you there when you’re being problematic. The more often sick, the more loved.”

Typical traits or attributions by others: Adventurous, impulsive, spirited, attention-seeking, narcissistic, unreliable, airs and graces, superficial, manipulable, charming, impatient

Application

Similar to the question about what good criticism or good communication is, as covered in my review of the book The Culture Map, the model highlights what the limits of empathy can look like and where they originate: Characters of one side feel like they have the cure for the other. That is because their fears and feelings are not only very different - they never felt each other’s emotions the same way in comparable situations like this.

From the perspective of the diagram, Riemann’s model has a striking similarity to the DISC model which is more internationally known. But Riemann’s model is not designed to match people with lists of traits to classify them in isolation (although you can always analyze your own fears, use the model to help yourself understand the underlying causes and improve your daily interaction with the world at work or in relationships). Every human has traits from all the presented poles at the same time. It’s the personal weighting of each trait that makes the character. The Swiss psychologist Christoph Thomann extended this model to the Riemann-Thomann model: The most obvious changes are that he substituted the pathological terms schizoid, depressed, compulsive, and histrionic with the softer terms distance, proximity, continuity, and change (as already reflected in this article). He also suggests that people might have different positions in the model at work than in private life. This way the model has less of a judging character when used to assess people. As a couple therapist and later conflict moderator in companies, he demonstrated how to use it to arrange people relative to each other to understand their conflict potential.

If you identify someone as more of a proximity-continuity type in comparison to someone else who is more of a change-distance type, it becomes relatively simple to foresee the kinds of conflicts they will have with each other at work or in their private life. In a conflict between such a pair, the conflict resolution must begin with strengthening the bond for the proximity person, while the distance person first needs distance to recover. This example models a deadlock that is often easier to solve at work than in romantic relationships.

Another conflict example would be: What happens if you put one or more distance-change types of persons together with an existing established team of proximity-continuity types and give them the mission to introduce some complex change? It is not unlikely that the productivity of the group will be reduced while the team gets stuck in discussions between the people who want a plan for everything and the ones who think that you need more of an open experimental approach because trying out new things will produce new unforeseeable problems where planning doesn’t help you much. Most likely, no one will say “I feel uncomfortable like this, can you please at least give me something to hold on” but instead non-productively fantasize bad intentions or cram out some prejudices.

In such cases, the model helps find out why people don’t want things and how to present each other’s positions in a way that doesn’t trigger the other side’s fears. The more people in the team educated themselves with such models, the less need would be for a manager or moderator to solve such crises.

Also, if someone works together with a happy team of relatively homogeneous character traits and realizes that he/she is in the opposite corner of the Riemann coordinate system than most of the others, then the Riemann model provides new ways to explain why such an environment feels exhausting or even toxic to them without even anyone having about bad intentions. In such cases, the model provides some guidance in describing why some team constellations simply are less efficient or effective than others, and how to compose teams with what combination of personality types for which kind of task. If all advice fails, the book gives a good decision basis on whether to leave a constellation.

If you speak in front of a group or sell products or ideas, having some knowledge about the character types of the key people in the room will also help present your subject in the right way by carefully circumnavigating what might trigger their discomfort.

The Riemann Model is also a useful complement to the Situational Leadership model for managers: This model prescribes that leaders should adapt their leadership style to the maturity of the people or group they manage. At the same time, the Riemann Model suggests that the style of interaction with people and groups should be chosen by their personality traits. From that perspective, the situational leadership model provides a temporal view that develops over time, and the Riemann model a spatial view that considers the needs of the underlying character.

Summary

Over the years, it kind of became my thing at work to introduce new technologies or ways to solve challenges - having a tendency towards the distance and change types from the book - this always happened with the best intentions to improve my customer’s/team’s/company’s agility, ability to innovate, etc. Reading this book helped me understand better why and how other people sometimes see this as a curse or threat instead of a blessing, and how to present ideas to reach more people in the intended ways with fewer misunderstandings. Also, while founding my own company together with colleagues, I faced new challenges in human interaction e.g. by becoming manager of a team, etc.

Most popular science books that originate from psychology or social sciences don’t contain completely new things: As an “experienced human” we have seen most situations already. What such books provide are views on the situations/challenges that are already known, with a new structure that helps describe challenges and find better solutions. Not only in that regard I found this book to be a fascinating and inspirational read. To me, reading this book equals never again having no explanation for the strange behavior of others that have a completely different character. Such insights don’t automatically provide solutions but at least extend limits of empathy.

The model provides useful insights but less actionable advice. For more detailed advisory I suggest reading Nico Fleisch’s book about the Riemann-Thomann Model for which I, unfortunately, did not find any English version.

Humans who work with other humans should read this.